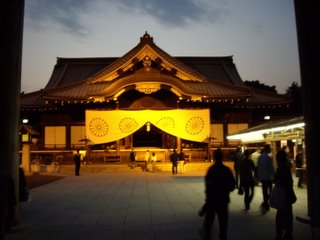

On a cool rainy morning of October 17 Prime Minister Koizumi made a surprise, but not unexpected fifth visit to Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo. It was the first day of the Shrine’s autumn festival, but not an especially significant anniversary of World War II. In August many watchers held their breath not knowing if he would make an appearance at the Shrine on the Sixtieth Anniversary of the war. He didn’t. Shortly thereafter, he called a snap election after dissolving the lower house of the Diet in order to push through his privatization of the Post Office. Throughout the election he was asked if he would visit and replied only that he would make an “appropriate” decision.

Chinese and Korean diplomatic meetings were cancelled. Chinese and Korean citizens protested in the streets. The reaction was harsh and immediate. Every time the Japanese Prime Minister visits the shrine Asia reacts. Just as the flap of a butterfly’s wing in Brazil can cause a typhoon in Taiwan, so too does Koizumi’s visit in Tokyo cause a storm across China and Korea.

How do we explain the interactions between these nations in international relations terminology? Is this simply diplomatic posturing, or does Koizumi’s visit represent a serious international relations crisis? How can International Relations theory answer this question: Why does the historical legacy of World War Two continue to adversely affect international relations in East Asia and why is it of such concern?

Why visit the Shrine?

Christopher Bertram, former director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin and current Steven Muller Chair for German Studies at the Johns Hopkins University Bologna Center, points out in the Taipei Times, “Koizumi's visit to the shrine, officially presented as that of a private citizen, was intended to impress the Japanese public, regardless of its effects abroad.”[1] For Koizumi, it is a private and domestic issue. Some LDP members have declared that it is a domestic issue and that protests by China and Korea are interference in domestic issues. For realists too, this is a domestic issue and does not matter. This analysis requires that Koizumi’s reasoning for visiting the shrine is rationally based, and has a purpose. It is not.

Why does he do it? According to an official statement shortly after his first visit in 2001, he declared:

During the war, Japan caused tremendous sufferings to many people of the world including its own people. Following a mistaken national policy during a certain period in the past, Japan imposed, through its colonial rule and aggression, immeasurable ravages and suffering particularly to the people of the neighboring countries in Asia. This has left a still incurable scar to many people in the region.

Sincerely facing these deeply regrettable historical facts as they are, here I offer my feelings of profound remorse and sincere mourning to all the victims of the war.[2]

Although many credit Koizumi’s desire to attract voters of the Japan Association for the Bereaved Families of the War Dead for his visiting Yasukuni, it is not clear that this mattered in his last, post election visit. It is more widely believed that he visits Yasukuni out of pure personal conviction.

In February 2001, shortly before he became Prime Minister, he visited a memorial to Kamikaze pilots in Kagoshima Prefecture. The letters of the doomed pilots to their mothers left him crying. In April 2001, he notified the Japan Association for the Bereaved Families of the War dead that he would visit Yasukuni. A few weeks later, he was elected Prime Minister. House of Representatives member Koichi Kato describes Koizumi as a “politician who depends much on emotion and intuition instead of logic and reason when making decisions.” He follows his heart to Yasukuni.

When Koizumi first visited the Yasukuni Shrine in 2001 rallies in neighboring South Korea and China were very passionate. Then, more than one thousand protesters gathered in central Seoul to denounce the prime minister’s visit to the shrine. Japanese flags were burned in the streets and many young men severed the ends of their fingers in protest.[3] In April of 2005 Anti-Japanese protests rocked China. Tens of thousands of people gathered in front of Japanese diplomatic facilities to lob eggs, stones, and plastic bottles at the buildings. Japanese made cars and businesses, many Chinese owned, were vandalized. The protests were precipitated by the approval of a nationalistic textbook in Japan, an issue directly related to the lack of atonement the shrine visits represent.[4]

Diplomatic protests have become standard practice. However, this goes further than diplomatic posturing. The Christian Science Monitor reports that relations between Koziumi and Jintao are cold, and that the two are barely on speaking terms. Bilateral talks have been refused since 1999. South Korea has followed suit, with the Republic of Korea’s Prime Minister recently announcing the end of all bilateral talks, even on the sides of international meetings. Diplomatic and public relations with its neighbors could not be much worse.

The business community is becoming greatly concerned, just as business opportunities are opening up in China. After Koizumi’s most recent visit Japan Association of Corporate Executives Chairman Kakutaro Kitashiro warned Koizumi to consider the risk it poses for Japan’s strategic interests.[5] Already, the Chinese have used the threat of canceling or not signing large contracts with Japanese companies as punishment for Koizumi’s visits to the shrine. Notably, the Chinese are looking more closely at French high-speed train technology rather than buy Japanese.[6]

Christian Caryl points out in Newsweek that a major dynamic is the changing face of Asia. As the middle classes of Japan’s neighbors grow, the tacit agreement to ignore the history in return for aid is no longer valid. As she quoted, South Korean Prime Minister Lee Hae-Chan said: “We're not asking for money from the Japanese government. We have enough money. What the Korean government wants from Japan is truth and sincerity, and [a commitment] to help develop healthy relations between the two countries.”[7]

Image and Realities of Japan

East Asia today is increasingly well placed to become one of the most developed regions in the world. The formation of a future East Asian community is a common goal for the countries of the region. At this historic turning point, Japan is determined to contribute constructively to the future of East Asia and, to that end, places great importance on its friendly relations with neighboring Asian countries, including China and the Republic of Korea. Japan has demonstrated this spirit through its actions over the past 60 years. The task of further strengthening its relations with neighboring countries and contributing to the peace and stability of the East Asian region is one of Japan's most important policy priorities.This, the official message of the Japanese government, is in line with the outward image Japan wishes to promote. Only one other nation besides Japan has a “peace constitution.” Costa Rica and Japan both have officially renounced war as a manner of settling international disputes. Japan’s experience of utter defeat, and America’s determination to democratize, disarm, and decentralize Japan, led to writing of Article IX of the Constitution:

-- Basic Position of the Government of Japan Regarding Prime Minister Koizumi's Visits to Yasukuni Shrine, October 2005

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.Masaru Tamamoto, Senior Fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, states that, “More than any clumsy words of apology, renunciation of war has been Japan’s sure way to atone for the guilt of empire and the Second World War.”[8] According Nicholas Kristof, “Japan is kept so shaken and frail by its wartime legacy that it will be incapable of aggression for decades to come.”[9] In this manner, Japan’s peace constitution serves as a major barrier for Japan’s aggression, both internationally as a symbol of Japan and domestically as a barrier to war.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized. – Article IX, The Constitution of Japan

Evidence shows that Japan has ignored the pacifists, and slowly hallowed out the constitution to respond to its realist tendencies. The ink had barely dried on Japan’s new constitution before the Korean War broke out and led to America’s “reverse course’ vis-à-vis Japan. Richard Nixon called Article IX a mistake in 1953 during his vice presidential visit.[10] Since that time, Japan has debated the reality of Article IX and the nature of its security, and slowly the constitution has atrophied. As McCormack notes, “The gap between the pacifist principle of the Constitution and the reality, once established, grew and widened.”[11]

Evidence shows that Japan has ignored the pacifists, and slowly hallowed out the constitution to respond to its realist tendencies. The ink had barely dried on Japan’s new constitution before the Korean War broke out and led to America’s “reverse course’ vis-à-vis Japan. Richard Nixon called Article IX a mistake in 1953 during his vice presidential visit.[10] Since that time, Japan has debated the reality of Article IX and the nature of its security, and slowly the constitution has atrophied. As McCormack notes, “The gap between the pacifist principle of the Constitution and the reality, once established, grew and widened.”[11]With the aging of the population, Japanese citizens who witnessed the war firsthand and participated in these debates are disappearing. As quoted by the Christian Science Monitor, Masao Kunihiro said, “I'm a dyed-in-the-wool pacifist. My house in Kobe was burned during the war. But I'm like a dodo bird. I feel that pacifism here is on the edge of extinction.”[12] Japanese youth do not feel a connection to the war, and do not wish to be blamed for the atrocities of their grandfathers.

What happens when this barrier is removed? What does this mean for stability in East Asia? If Japan has fewer pacifists, does the chance for war increase? This is the dilemma for constructivists in explaining why there is continued peace in and around Japan.

There are many changes in the security fabric of East Asia. William Rapp of the Strategic Studies Institute notes:

The current era of North Korean nuclear brinkmanship and the global war on terrorism are likely to provide the impetus for Japan to take major steps towards “normal nation,” and then towards significant maturation of, and greater power sharing within, the U.S.-Japan alliance.[13]These changes have already begun to take shape, and Japan is moving towards “normal nation” status.

The United States has worked to pressure Japan to make these moves, and Japan itself has sought to achieve a more active role in international affairs. The overseas deployment of the Self Defense Forces in Iraq demonstrates the commitment of the current government to these changes. Thomas Wilborn of the Strategic Studies Institute remarks that although much pressure for Japan’s shift from “idealistic pacificism” to a realist defense policy is the result of U.S. pressure, much also comes from internal pressures.[14] Lieggi and Wuebbels note that, “A new generation of Japanese politicians, taking an increasingly realist approach to defense policy, is gaining prominence in the Diet.”[15]

This movement to the right, and the loosening of Japan’s military constraints are furthered by the debate over the revision of the constitution. The Liberal Democratic Party has approved its draft of the new constitution, and specifically promotes the alteration of Article 9. In particular, they wish to recognize the existence of a Japanese military and eliminate the ban on collective self-defense.[16] As a result, Japan today has one of the largest, well-funded, technically advanced militaries in the world.

The Reality – Will Japan Remilitarize?

In order to give lip service to the peace constitution, Japan has limited its military expenditures to less than 1% of its GDP. Only a few times has it surpassed that level, and only by a fraction. In spite of this, 1% of the worlds second largest GDP is a considerable sum of money. In July 2005, according to the World Bank, Japan’s GDP was approximately $4.6 trillion, leaving $46 billion for military expenditures. With this sizable amount of money to spend on the military, even at 1%, Japan has the fourth largest military expenditure in the world. This is smaller than only the United States, United Kingdom, and France.

Relative to its large budget, the number of uniformed military personnel in Japan is relatively small. The total authorized personnel strength for Japan is 262,073 personnel in all branches of the Self Defense Forces. Staffed around 90%, the actual number of forces is just over 236,000 personnel. In comparison, this is smaller than France, but larger than Italy and the United Kingdom.[18] However, this is significantly smaller than all of Japan’s neighbors, including China (2.4 million), North Korea (1 million), Russia (900,000), and South Korea (665,000). Much of this is to do with the extraordinary costs of equipment and personnel costs in Japan as compared to other countries including the US. For example, vehicle costs are three to ten times that of the US military.[19] On a Purchasing Power Parity basis, Japan Drops from fifth to eighth in spending, smaller than the US, China, India, Russia, France, the UK, and Germany. However, this is still larger than most of the world.

Relative to its large budget, the number of uniformed military personnel in Japan is relatively small. The total authorized personnel strength for Japan is 262,073 personnel in all branches of the Self Defense Forces. Staffed around 90%, the actual number of forces is just over 236,000 personnel. In comparison, this is smaller than France, but larger than Italy and the United Kingdom.[18] However, this is significantly smaller than all of Japan’s neighbors, including China (2.4 million), North Korea (1 million), Russia (900,000), and South Korea (665,000). Much of this is to do with the extraordinary costs of equipment and personnel costs in Japan as compared to other countries including the US. For example, vehicle costs are three to ten times that of the US military.[19] On a Purchasing Power Parity basis, Japan Drops from fifth to eighth in spending, smaller than the US, China, India, Russia, France, the UK, and Germany. However, this is still larger than most of the world.This discrepancy can also be explained by the use of high technology in the Japanese military. Since the early eighties Japan has invested in the newest military technology, often with the support of the United States. For example, the Japanese self defense forces fly F-15J aircraft,[20] sail an advanced equivalent of the Arleigh Burke Class Destroyer (like the USS Cole),[21] are building a small aircraft carrier they are calling a destroyer,[22] and are establishing a new elite military unit like America’s Green Berets to fight terrorism.[23]

In October of 2000 the Institute for National Strategic Studies issued ‘Nye-Armitage Report’, a blueprint for the Bush administrations Japan policy. It described the Japanese Self Defense Forces as “well-equipped and competent military.”[24] Only the United States and Japan possess the AEGIS Radar Systems found on these Destroyers.[25] Few countries have advanced fighter jets such as the Japanese F-2 or US F-16, and even fewer countries have aircraft carriers. Its new Destroyers (sic aircraft carrier) will be the largest warships since World War II at 13,500 tons. This is large enough to carry 12 helicopters, and will be larger than aircraft carriers owned by Spain or Thailand.[26] Although there are no plans to do so, it is also capable of carrying vertical takeoff jets like the British and American Harrier.

Japan can also boast domestic production of these advanced military technologies. Mitsubishi builds the F-15J and much of its internal technology. Likewise, Japanese Naval vessels such as the “Kongo” Class Destroyer are based upon American designs and are manufactured in Japan.[27] The only weakness to the modern Japanese military is that it relies heavily on the US defense industry for design work, but much of the actual construction is conducted in country. A recent example of this arrangement includes a project by United Defense to build a component of shipboard vertical launch missiles. Japan will fund 26% of the project.[28]

The Theories

Both realist and constructivist scholars have addressed the source of Japanese security policy. For constructivists, Japan is a prime example of how norms and domestic politics can restrain tendencies for Japan to rearm itself. Jennifer Lind says, “Constructivist scholars argue that since World War II, domestic Japanese norms have prevented major expansion of Japanese military capabilities and roles.”[29] However, for realists Japan is or wants to be a “normal nation” that seeks to secure itself with military power. Lind calls this passing the buck: “Both schools [offensive and defensive realists] argue that security concerns trump other factors in the development of foreign policies.” Evidence shows that both are taking place.

John Ikenberry points out that there are reasons to believe that realism is a valid explanation for Asian-Pacific International Relations Theory: “The region [East Asia] continues to hold the potential for traditional security conflicts that result from dynamics such as major power rivalry, competing territorial claims among sovereign states, and the operation of the security dilemma.”[30]

"However, it is also true that Koizumi's visits to the shrine are not in Japan’s interest. A Brookings Institution Report says it well: “Article Nine is the backbone for an attractive Japanese national identity that stands foursquare for peace and non-proliferation—two highly admirable values. It is, moreover, a potential "soft power" resource—even if it has never been wielded to great effect.”[31]

Katzenstein and Okawara call for an eclectic analysis of East Asian security. Specifically, they call for a problem driven approach to solving the problems of East Asia. Neither realist theory nor the constructivist approach alone can explain why Japan has one of the strongest militaries in the world or why and with what result the Prime Minister of Japan will visit Yasukuni Shrine. An advantage Katzenstein and Okawara note is that “a problem-driven approach to research has one big advantage. It sidesteps often bitter, repetitive, and inherently inconclusive paradigmatic debates.”[32]

Japan is a land of contradictions, and the paradigm of pacificist state with a strong army is yet another contradiction. In order to understand this phenomenon it is not possible to rely upon a single strain of International Relations theory. International, domestic, security, cultural, and historical considerations are all critically important in the understanding of not only the potential for war in East Asia, but also for understanding why Koizumi goes to Yasukuni.

End Notes

[1] http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2005/11/01/2003278307

[2] “Statement by Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi” Speeches and Statements by Prime Minister Homepage. August 13, 2001. http://www.kantei.go.jp/foreign/koizumispeech/2001/0813danwa_e.html

[3] Jong-Heon, Lee. “Anti-Japanese sentiment surging in S.Korea.” United Press International. August 14, 2001.

[4] http://observer.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,6903,1461648,00.html

[5] http://www.japantoday.com/e/?content=news&cat=3&id=352320

[6]http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2004-02/24/content_308867.htm

[7] http://japanfocus.org/article.asp?id=428

[8] Tamamoto, Masaru. “A Land Without Patriots.” World Policy Journal. Fall 2001. pp. 33-40

[9] Kristof, Nicholas D. “The Problem of Memory.” Foreign Affairs. Nov/Dec 1998; 77, 6.

[10] McCormack, Gavan. “The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence.” London: M.E. Sharpe, 1996. p. 191.

[11] Ibid., p. 193.

[12] Marquand, Robert. “Pacifist Japan beefs up military.” The Christian Science Monitor. August 15, 2003. http://www.csmonitor.com/2003/0815/p06s02-woap.html

[13] Rapp, William E. “Paths Divergent? The Next Decade in the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance.” Strategic Studies Institute. National Defense University. 2004. p. 7. http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/pubs/2004/paths/paths.pdf

[14] Wilborn, Thomas. “Japan’s Self-Defense Forces: What Dangers to Northeast Asia?” Strategic Studies Institute. May 1, 1994 p. 21.

[15] Lieggi, Stephanie and Mark Wuebbels. “Will Emerging Challenges Change Japanese Security Policy?” Center for Nonproliferation Studies. December 2003. p. 1.

[16]http://www.asahi.com/english/Herald-asahi/TKY200510310093.html

[17] www.sipri.org/contents/milap/milex/mex_major_spenders.pdf

[18] “The World Fact Book.” Central Intelligence Agency. http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/

[19] http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/budget.htm

[20] “F-15 Eagle.” Military Analysis Network. Federation of American Scientists. http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/ac/f-15.htm

[21] “DDG Kongo Class.” Global Security.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/kongo.htm

[22] Sherman, Kenneth B. “A Carrier Named Destroyer.” Journal of Electronic Defense. March 2004. Vol. 27, Issue 3, p. 24.

[23] “Japan to Create Its Version of Green Beret Unit.” Jiji Press English News Service. Tokyo: March 18, 2004. pg. 1.

[24] “The United States and Japan: Advancing Toward a Mature Partnership.” INSS Special Report. National Defense University. www.udu.edu/ndu/SR_JAPAN.HTM. October 11, 2000.

[25] Glosserman, Brad. “Making History the Hard Way.” Comparative Connections. Pacific Forum: CSIS. 4th Quarter, 2001. http://csis.org/pacfor/cc/0104Qus_japan.html

[26] Moffett, Sebastian and Martin Fackler. “Active Duty: Cautiously, Japan Returns to Combat, IN Southern Iraq.” Wall Street Journal. January 2, 2004. pg. A.1

[27] “DDG Kongo Class.” Global Security.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/kongo.htm

[28] “US DOD: Contracts.” M2 Presswire. Coventry: March 9, 2004. p. 1.

[29] Lind, Jennifer. “Pacifism or Passing the Buck?” International Security. Sumer 2004, 29:1, pp. 92-121

[30] Ikenberry, G. John and Michael Mastanduno. “International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific.” New York: Columbia University Press. 2003.

[31] http://www.brookings.edu/fp/cnaps/events/20041215.htm

[32] Katzenstein, Peter J and Nobuo Okawara. “Japan, Asian-Pacific Security, and the Case for Analytical Exlecticism.” International Security. Winter 2001/02, 26:3, pp. 153-185.

No comments:

Post a Comment